Volume 3, Number 4, June 2005

[UA Universe] [Ask the Doctors] [Digital Minds] [Analog Obsession]

[Support Report] [The Channel] [Plug-In Power] [Analog Ears] [Featured Promotion]

[Graphic-Rich WebZine]

[Back Issues] [UA Home]

Bill Putnam, Part 2

[Continued from Part 1]

By Jim Cogan

|

|

Bill Putnam Sr. (left)

|

So many forces in play: the rise of the hi-fi consumer (the sort of man who read Mr. Hefner's mag); the emergence of the indie label (most notably Chess and Vee-Jay); the increase in sales and stature for Chicago-based Mercury Records; the networking with industry A&R men and producers; the recruitment of key technical personnel, such as Emery Cook and Jim Cunningham; and the increased exposure to a variety of recording scenarios. All of this meant explosive growth for Putnam, Universal Recording and United Audio.

"People forget, Chicago became the place to record in the '50s," says New Yorker Phil Ramone. "All of these labels, like Vee-Jay and Mercury [and Chess], started coming around."

By the end of the '40s, Putnam had outgrown his tenure at the Civic Opera House, scene of his mega-smash "Peg o' My Heart." With the proceeds from this 1,500,000-selling single on Putnam's own Universal Records, a change in venues was inevitable. Putnam looked to the east-if only a few blocks-to the Magnificent Mile of Michigan Avenue, where there were more clubs, more action. He scouted a building on Ontario Street, a bustling thoroughfare on the near North Side.

“The floodgates opened, and Putnam was thriving as the owner of the country's hottest facility.”

He was juggling like a madman. Producer, lyricist, label owner, engineer, studio owner and technical designer were all titles to which he answered. It was at the Ontario Street space, and with the help of Cunningham and Cook, where Putnam began to make serious breakthroughs in isolation, mastering and reverberation. He built two rooms here, A (25x40x15 feet) and B (15x20x12 feet), along with two mastering rooms: one stocked with Scully lathe and Grampion heads, the other a "home-brew" belt-driven turntable with Olsen feedback cutting heads.

This studio, in operation from roughly 1950 to 1955, was a pivotal juncture in Putnam's career. As a result of meeting Decca Records A&R man Tutti Camaratta (himself a studio recording legend who went on to own and operate Sunset Sound in Los Angeles), he began producing "hillbilly" acts; London-based Decca badly wanted C&W acts, so Putnam recorded Hank Williams, and also wrote for and produced more artists for Decca. Yet, he never strayed far from his first musical love, jazz: Stan Kenton, who likewise stretched the boundaries of his profession, became the first jewel in a crown of royalty that started to flood Universal.

When Kenton and his progressive, wailing band came in to record in 1951, the two hit it off immediately. "We had gone in to record with Bill, and Bill had everything set up" recalls Murray Allen, then a member of Kenton's band and the man who would one day own

Universal Recording. "Kenton called in to Bill, 'Bill, how's everything in there?' and Bill replied, 'Everything's perfect until the music starts.'"

Thus began an association that would last until Kenton's death. These two mavericks were perfectly suited for each other. For these sessions, Putnam wanted the sound to be as fresh and bold as Kenton's arrangements. So he began to address several aspects that would have profound effects on how records sound.

Putnam devised a band shell for strings that was a mainstay for almost two decades. In addition, he built a drum shed for the isolation of drums to be used for the Kenton recordings. He conducted the first 8-track experiments, which featured a staggered head with a signal-to-noise ratio of 30 dB. But most significantly, perhaps, was the creation of another "home brew": a custom console, complete with rotary faders, 12 inputs, preamps and dedicated echo sends.

"Bill Putnam was the father of modern recording as we know it today" says Bruce Swedien. "The processes and designs that we take for granted-the design of modern recording desks, the way components are laid out and the way they function, cue sends, echo returns, multitrack switching-they all originated in Bill's imagination. That's pretty serious." The home-brew console was the precursor to the vaunted Universal 610 console, which is the precursor to whatever console you are using right now.

As mentioned in Part One, Emory Cook was a fellow pioneer who joined forces to make Universal the premier mastering house in the country. In the early '50s, folks such as Cosimo Matassa in New Orleans and Sam Phillips in Memphis shipped their tracks up to Chicago to have the hottest masters cut. In fact, due to the innovations with half-speed mastering that Putnam and Cook were employing (another first), Mercury contracted Putnam to master their remarkable Living Presence hi-fi recordings, featuring, most notably, some of the early stereo recordings to capture the powerful Chicago Symphony Orchestra as recorded by Lewis Layton.

The floodgates opened, and Putnam was thriving as the owner of the country's hottest facility. Universal's growth was made possible by the confluence of these factors: the road bands of Basie, Kenton and the like; and the home-grown labels such as Mercury and the nascent R&B/blues scene that was emerging on the strip known as "Record Row" on south Michigan Avenue, home of Chess and Vee-Jay. From these two labels, Putnam recorded the urban funk of Little Walter, Willie Dixon, Jimmy Reed and Muddy Waters, as well as the flash-in-the-pan "rock 'n' roll" thing with Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley. This was in addition to recording Hank Williams for Decca and Spike Jones for Liberty. "We were on a roll" was how Putnam put it years later. "With the extraordinary growth of Ontario Street, I decided to build my dream room."

The '50s were a fertile era in the development of studio construction. Many of the most storied American studios were built at this time: Capitol Tower; Chess; Rudy Van Gelder's studio in Englewood Cliffs, N.J.; Sun in Memphis; and Criteria in Miami.

Universal Recording, at 46 East Walton, may well be the most mythical studio of them all. Swedien, who was hired by Putnam to work the "B" room, has never been able to contain his enthusiasm for that particular space. "This was a magnificent room" he says. "The dimensions of the 'A' room were 80 feet by 60 feet, with 30-foot-high ceilings. Floating floors, built on cork, suspended walls, variable acoustics with rotating panels. One of the best-sounding rooms in the world."

By 1955, the move to 46 East Walton was complete, and the studios were thrumming with jazz, swing, pop and R&B. Top producers from Mitch Miller to Quincy Jones were lining up to work with him at Universal. However, far from being too busy or too cool, Putnam was warm and inclusive. An example of his nature comes again from Swedien, who, after learning that Putnam created "Peg o' My Heart" would not stop bugging his parents with, "Bill Putnam this, Bill Putnam that." On a business trip from Minnesota, Swedien's parents decided to look up this Putnam fellow. Such was the openness of the man-the hottest producer/designer/engineer in America-that in the middle of a Patti Page session, he welcomed the young Swede's parents-strangers-off-of-the-street and into the control room as if they were old friends. They were sold; their boy could come down and work here.

Revenues were up 30% to 40% each year. Universal's staff was expanding. Again, in addition to the massive "A" the "B" rooms were cutting-edge mastering rooms, as well as state-of-the-art echo chambers. "Everything at Universal was first-rate, state-of-the-art, from the equipment to the staff" says the "Iceman" Jerry Butler, who would record one of the very first "soul" records ever, For Your Precious Love, with Putnam at Universal.

One artist who had enjoyed the room-and its designer-was the immortal Duke Ellington, the greatest composer/arranger in American music history. Putnam, who recorded a total of 250 tracks for him, described a session with Duke as, "like the last act of a Russian opera. It was no doubt the most organized musical chaos that you ever heard until all of the pieces got glued together. It then became musical ecstasy. To be around this great man was its own reward."

So this was Putnam's world in the mid-'50s: Mahalia Jackson to Hank Williams, Spike Jones to Bo Diddley. Erasing and re-penciling the boundaries of acoustic design, console design, isolation, mastering and miking. Still, he was not the first, nor would he be the last, engineer to put things such as home and health on the back burner. Smoking, drinking and long hours were exacting a toll. Putnam's marriage was not in good shape. But now he heard new whispers: "Come out to Los Angeles, the Mecca of recording. You'll mop up."

"Things were really moving along: Many of our clients, who were owners of record labels, urged me to start a studio in Hollywood" recalled Putnam in the early '80s. "I had to make a decision whether to remain the 'big frog in the small pond' or take the giant step. This meant I would be going head to head against the legendary Radio Recorders, who were the giants of the independent recording studios. I was about to take a step to find out where I really stood in the pecking order."

So, after an unprecedented 10-year run in Chicago, Putnam sold his interest in Universal in 1957. He handed the baton and his Rolodex of clients to his protégé, Swedien, in a manner that was characteristic: "Bill had worked this out beforehand" says Swedien. "He told me to sit at the console and record Kenton's band while he stood in the back of the control room and smoked. He told me that he was going to the john and left me alone in the control room. The next time I saw him was five years later in Los Angeles."

Universal in Chicago would be a force for a decade to follow, with Swedien recording a slew of hits such as "Big Girls Don't Cry" by the Four Seasons, "Duke of Earl" by Gene Chandler, "It's in His Kiss" by Betty Everett and "Higher and Higher" by Jackie Wilson, not to mention the incredible Chicago soul records of Curtis Mayfield & The Impressions.

It was 1958. Putnam, who worked regularly with Basie and Ellington, was doing a session for a couple of kids. "I was 18 at the time" says Butler. "Curtis [Mayfield] was only 15. We came in with a song that Curtis had written called 'For Your Precious Love.' Because of some contractual obligations, it was decided that union musicians were gonna play on the track. Well, we ran the song down to show the musicians, and Putnam turns to Curtis, who had been playing the guitar, and says, 'That's the heart and soul of your song right there in that guitar.' So right there, Curtis' guitar became the glue. Putnam spotted that."

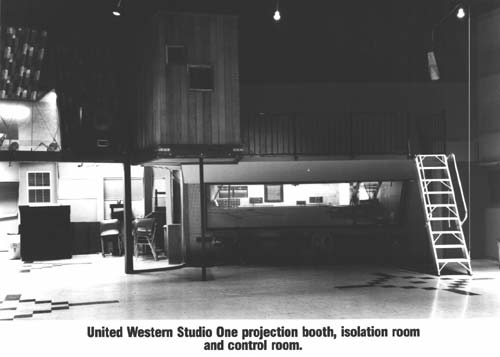

1958. Putnam begins construction on the former Douglas Fairbanks soundstage at 6050 Sunset Blvd. He'd brought along Curt Esser, the architect behind his innovative Universal studio in Chicago, to go one better in Hollywood. Together, and with the assistance of another Chi-cronie, Jim Cunningham, United became this massive space in which Studios A (60,000 cubic feet) and B (approximately 35,000 cubic feet) share a roof with a 3,000-cubic-foot stereo echo chamber, maybe the best-sounding stereo chamber ever in an American studio. This 15,0000 square feet of audio Valhalla-comprising three studios, a mixdown room, three mastering rooms and a manufacturing plant-would bring together the best of the West Coast engineers, and a team of managers and designers to topple the once dominant Radio Recorders. But Putnam wasn't finished. By 1960, he acquired the former Radio Center Theater, at 6000 Sunset, to form Western Recorders. As with United, there were two large rooms, Studio 1 (approximately 65,000 cubic feet) and the slightly smaller Studio 2. "Studio 3 was made from what was left over" Putnam would recall with a touch of irony. "As fate would have it, this was the studio that became legendary, to the extent that this room would be copied by Wally Heider [he even named it Studio 3, which was very flattering] in the '70s, as well as two other studios in the U.S. and Canada, each publicizing that it was a replica of the famous Studio 3 in Hollywood." Although many of the classic '60s groups such as The Turtles, The Mamas & The Papas, The Lettermen, The Association, Johnny Rivers, Glen Campbell and Jan & Dean made stellar tracks there, it's the timeless work of engineer Chuck Britz and auteur Brian Wilson (in particular, one of the most revered pop albums in history, Pet Sounds) that give the room its tiny shrine-like aura.

As the '60s began, Putnam became an unofficial member of the Rat Pack. Legendary arranger Nelson Riddle made an introduction that would completely transform Putnam's world. In 1960, Frank Sinatra was arguably the most powerful man in show business. At first meeting, Sinatra instinctively sussed that Putnam wasn't merely a techie, but a fellow leader, a fellow swinger, becoming the only "technician" Sinatra ever became true pals with. Coincidentally, Sinatra's contract was up with Capitol. He started his own label, Reprise, which would record all of its seminal tracks at United's A and Western's 1 rooms, including monster hits like "It Was a Very Good Year" and "Strangers in the Night." United's kingdom housed the Reprise offices for Putnam's new buddy; in fact, Sinatra, who epitomized the evolution and excellence of modern recording like no one else, soon depended on Putnam to do all of his sessions, becoming pissy if Putnam was busy with another artist. So he put Putnam on retainer to handle virtually all of his sessions from 1960 to 1964. More importantly, the chairman of the board introduced him to his assistant, Miriam, or "Tookie" as she was known by friends.

Putnam, who had been recently divorced from his first wife, was suddenly in sync on every level of his new West Coast life. Demonstrating how a recording facility could be built and run, he'd gone head-to-head with Radio Recorders, the biggest independent studio in Los Angeles, and won. He finally found a woman who "understood what my business was about and what I was about." (They married and produced two children, Bill Jr. and Jim, both of whom would continue the Universal brand to the present day.) And, he was making cool records. Examples of Putnam and Sinatra collaborations at United/Western include Sinatra: Basie and Sinatra & Strings. They're textbooks on how strings, horns, brass, rhythm and vocal should be laid down.

As good as those early '60s tracks with Francis Albert are, Putnam's most iconic recording from the post-Chicago days was with another maverick on par with Sinatra, Kenton or Basie: Ray Charles. Brother Ray, who, like Sinatra, had left his longtime label (Atlantic) for ABC (Impulse), was itching to do something new. Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music, Vol. 1 was new. Cross-pollinating country with the blues, Rays' mournfully jazzy "I Can't Stop Loving You" skyrocketed to Number One on Billboard's Top 100. With Sid Feller overseeing proceedings and Putnam perched behind his newly minted Universal 610 console, the LP was not only a commercial smash, but it also garnered the "Record of the Year" Grammy. Putman, now the king of Hollywood's recorders, snagged a "Best Engineered Song" Grammy nomination for the ring-a-ding-ding year of 1962. It lost out, alas, to another genre-bending act: The Chipmunks.

These were the good years: UREI and Reprise upstairs, humming along; Nat, Bing, Dino, Frank and Ray in United (now Ocean Way), while the newer breed of hit-makers, like the Beach Boys and The Mamas & The Papas, were locked into Western 1, 2 or 3 (now Cello); and the finest engineering staff ever assembled with Bones Howe (the Fifth Dimension), Lee Herschberg (Sinatra), Heider (Crosby, Stills and Nash), Chuck Britz (the Beach Boys) and the young Allen Sides; the sweetest echo chambers on the planet, so deigned by Brian Wilson, cunningly crafted by Putnam and Jim Cunningham; and, rooms so acoustically marvelous, that they have gone virtually untouched by the present owners some 40 years later.

|

Talk about shrewd. In the early '60s, stereo was roughly at the same evolutionary spot where 5.1 is today. Label owners finally got hip to marketing and releasing stereo product, except that they had none. Or did they? Like Swedien, Ramone and Tom Dowd, Putnam had surreptitiously been running simultaneous stereo mixes along with the expected mono masters for a couple of years. When the labels got wind of this, they offered to pay for the tape. No dice, said Putnam. "However, I will let you pay me for the studio time."

During the late '70s and into the early '80s, Putnam slowed down, due somewhat to ill health, but also to the changing nature of the business. He explained, "Making records in the 2- or 3-track era was a heck of a lot of fun. In those days, when you walked out of the control room after a date, what you heard was what you got!"

As the recording environment evolved, no one stuck his finger into the air and forecast the winds of change more ably than M.T. Putnam. "When the independent producer became prominent, the old guard saw its demise. Then came the artist/producer-owned studio-style operation and the evolution of new technology, which brought the 'whiz kids' out of the woodwork, not just in Hollywood, but everywhere in the world. It became more and more difficult to compete in a fragmented market."

One of those whiz kids who carries the torch is George Massenburg, who tells of the time when he met with Putnam during this era of transition. "I had this console design that I went to show him. He was intrigued. He looked at the specs and said that he loved the design. Now, here is how he saw things: not, 'how long will this board take to amortize' or any of that stuff. Just 'how good does it sound, how well does it work?'"

In his twilight years, Putnam enjoyed the roles of mentor and elder statesman, appearing at a SPARS, NARAS or AES function. He'd had a pretty cool run: almost single handedly brought a bastard industry into its own realm; recorded the zenith of American music icons; and adored by literal and figurative offspring. Yet, it was always-always-about music.

"My dad took me to a Kenton memorial concert at the Hollywood Bowl" says his namesake, Bill Jr., who now heads Universal Audio. "All of the old guys showed up." When Bill Putnam, who just about cut his teeth on Kenton's music-before Hollywood, before Sinatra and all the money-heard the band's theme song, "Artistry in Rhythm" he broke down and cried.

During the course of this article, we spoke to many recording heroes. Each was asked what Putnam's legacy might be to today's mixers and engineers. The answers were often vague, probably because they hadn't time to think of a proper reply. So, here is what the man's legacy is: If you are <i>involved</i> with the bass line, and its player, and its sound, and its relation to the song, more than how it is being processed by Bill Putnam's 1176 limiter, its creator would probably nod approvingly. And shake out a new smoke.

Jim Cogan is the co-author of Temples of Sound (Chronicle Books, 2003). He is also an engineer/producer and educator.

Questions or comments on this article?