Artist Interview: Brad Plunkett

Former UREI Engineering Director Tells the Story Behind His Famous Inventions

by Marsha Vdovin

The recent passing of Bob Moog had me thinking a lot about the history of music and recording technologies. The technology pioneers of our industry have given us so much. So, I decided to interview Brad Plunkett this month. A longtime associate of Bill Putnam Sr., Brad created the Wah Wah pedal, among other devices, and engineered the LA-3, which UA is now reissuing.

|

|

From the December 1969 issue of the

United & Affiliates Newsletter |

When I was about 10 years old, I got an old short-wave radio from a neighbor. I was sitting out on the back porch and started listening to ham radio operators and radio Moscow and stuff like that. This was back in the early fifties, and I got very interested in radio. When I was 12 or 13, I got a ham radio license. Over a period of a couple years, I built some equipment of my own--very much the kind of thing that Bill Putnam did a few years earlier. He was a ham radio hobbyist, and as a matter of a fact Bill Jr. was too. The ham radio hobby led into me getting a job at a TV repair shop in the neighborhood where I lived in Van Nuys. I went in there when I was 13, and the guy said, "What can you do kid?" And I said, "Well, I can fix things." So they gave me a job fixing car radios, and this was of course in the vacuum tube days and they paid me a dollar and a quarter for each radio I fixed, I think. That turned out to be a really good job for a 13 year old. Pretty soon I had worked through the entire stack of radios and they had to teach me how to fix televisions. So I did all that through high school and that was how I got my spending money.

Toward the end of high school, I took a summer job at a company called Thomas Organ Company; they made electronic organs. There were a lot of people in our family that were musicians--not me, but everybody else in my family played an instrument. So I knew a little bit about music. I didn't know much about electronic organs, but I learned there over a summer, then went back to school. Every summer I went back there.

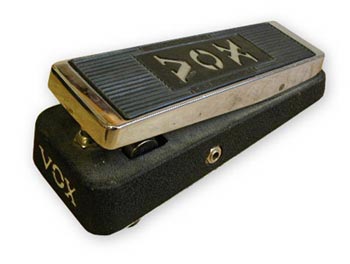

I had 10 years of electronics experience, even though I was only 20 years old. The job at Thomas got me involved in music, and somewhere around 1963 or '64, the owner of Thomas made a deal with a company in England called Vox, who made guitars and amplifiers. Vox had a deal with the Beatles at that time to promote Vox guitars and amplifiers. I think that they'd been given some free equipment early in their career, and as I recall they had a five-year deal with Vox, which was very good for Vox. We were developing in addition to electronic organs, portable organs for rock 'n' roll. We were doing guitar amplifiers and guitars I guess. One day, my boss led me to a guitar amplifier that had a feature on it called "midrange boost." It was a haystack equalization that you could move to four, five, six individual frequencies to change the tonality of the guitar amplifier. I think it was a Vox Buckingham but I'm not absolutely sure. His order was, "This rotary switch that we have for switching these frequencies on this equalizer is too expensive. I want you to take it out and figure out a way to replace it with a potentiometer. Up till that point, no one had really built a sweep equalizer, which is what the Wah Wah pedal really is.

|

|

Brad Plunkett is the inventor of wah

|

Then the next problem was how do you operate the thing if you need to turn the potentiometer at the same time you are playing the guitar and you already have both hands occupied. As I said before, we were doing electronic organs at that time too, and there was a portable organ within my field of view that somebody else was working on and he'd gone out to have a cigarette. I saw the volume pedal, the expression pedal sitting on the floor underneath this portable organ and I said, "John, why don't you go and grab that pedal and let's put the potentiometer in there." And so we did that, and in fact the Wah Wah pedal was built into the same piece of tooling that they had used for the expression pedals for portable organs up until that time. Anyway the thing took off like crazy. They sold millions of them.

Did you have a moment when you heard a song on the radio or saw someone play live when you realized that you changed the sound of rock 'n' roll?

Yeah. It actually didn't happen till a couple of years later. I was just sort of going along with it. I was aware of Eric Clapton and Jimi Hendrix and the fact that they were using pedals. I think somebody said to me one time, "You know Brad, I think that thing you invented changed music." It's a really fun thing to think about.

Did you get to meet any of those guitar greats? Did any of them come and pay homage to you?

[Laughs] No. I met James Brown; he came through the plant one time. That was kind of fun. I think the Dave Clark 5 came through. They are a group you don't hear about that much anymore, but they were contemporaries of the early Beatles.

In those days I was more into electronics, oscilloscopes and oscillators than I was into rock 'n' roll. I cranked the thing out and it left and I heard it on the radio and really, as I say, [it was] sometime later I realized that really had an effect--a major effect on the way music sounded for a long period of time. I still hear them now and then in jingles and that sort of thing.

You should feel proud.

I do. And it was a lot of fun. After that things kind of settled back into just being an engineer again. Except that it had given me a great deal of confidence to know that I could do something that was that cool and that important. I did some other things for Thomas; I think I developed the first drum machine or at least the first solid-state drum machine, which was an attachment for a Thomas Organ called the Band Box. I guess I had 10 or 15 patents when I left there.

In 1969, a friend of Bill's, who was also a friend of mine, approached me. And he told me about this company UREI which he had started in the back of the recording studio in Hollywood. He told me that they were interested in getting their product line expanded, and it turned out that I had some specific experience in automatically gain-controlled amplifiers, and some experience in a device called the light-dependent resistor, which was a key part of the optical limiters that UREI made. So I talked to Bill and he seemed like a really nice guy, and as it turned out he was a lot more than that--he was a legend. We made a deal.

At that time, I was ready to move on from Thomas because they'd been purchased by a huge washing machine company, and it looked like we were going to do washing machine timers and stuff like that instead of music. So I decided to bail. I went to work for Bill Putnam in October of 69. I was 29 years old. The optical limiter that you guys are making now, the LA-3, was the first product that I developed for UREI.

|

|

Brad designed a transistor based LA-2A

for Bill Putnam Sr.– the LA-3A |

Well, what happened with that was that UREI had been making the LA-2, which was a vacuum limiter, but still used the T4-B. Actually, it was called the T4-A optical attenuator. That design for the LA-2 had been purchased from a company called Babcock electronics. It has been purchased by Babcock from the estate, I think, of a fellow named Jim Lawrence who was the original inventor of the idea of using a light-dependent resistor as part of a gain control. It was kind of a goofy idea to do that, but it turned out it was a marvelous sounding thing. It had some characteristics that were unexpected that turned out to be really good.

The LA-2 was originally designed for the use of protecting radio stations from overmodulation. I don't think that Jim Lawrence was interested in recording, but it turned out to be a better thing for recording than it was for use in a radio station. Anyway, when I first started talking to Bill he told me he had this product with an optical attenuator in it, and as I said I had worked with light-dependent resistors before so I knew what he was talking about. He wanted me to change it from a vacuum tube product to a transistor product. I said, "Well if you tell me what it's supposed to do exactly, I'm sure I can make it work." He laughed and we sat and talked for an hour or so and he told me what he wanted. He gave me an LA-2 and I had a lab set up in my garage where I was living in Van Nuys. So I took it home and worked on it at nights while I was still working for Thomas/Vox. Over a period of time, I figured out how to do it and make it still sound right, and I sent the prototype in to UREI.

I waited for three months or so and didn't hear anything, and one day I finally called up and got a hold of the fellow who was the chief engineer then and I said, "I wonder if you have turned on that transistorized LA-2. I wonder if you have seen it." He said, "Yeah, I have seen it; it's sitting right here on the floor alongside my desk." I said, "Have you listened to it?" And he said, "No, and I'm not going to." I said, "Why? What's the problem?" He said, "Well, I don't believe in the idea of using optical attenuators. I think it's a silly idea, and I'm not going to waste my time with it." That ultimately ended up costing him his job.

Bill was very interested in optical attenuators. So, I talked to Bill later and I said, "It looks like the LA-3 is going to die." And he said, "Well, the hell it is," and the next thing I knew he cleaned out the engineering department and I was invited to come in as the Director of Engineering with nobody to direct, except for one guy who was kept around because he knew where some of the bodies were buried. He worked for me for a couple of weeks and then quit. So there I was Director of Engineering with nobody to direct.

So, we started bringing in some more people. I brought in a fellow that worked with me at Thomas who was really quite talented, and over a period of a few months we built up the department of, I guess, four or five guys, and started making products. During that period of time, of course, we did the packaging on the LA-3 and made it a half-rack size because we could because everything would fit. Just as it is now, in those days rackspace was at a premium, so it helped to make a product a little bit smaller. I don't remember how many of those things we sold, but we sold a gillion of them. It was very popular. Of course there always has been and always will be controversy about whether it sounds the same as an LA-2. I'm sure it doesn't sound exactly the same as an LA-2, but there are some people who like it better and there are some people who like the LA-2 better, and it was a very successful product for UREI.

How long did you work there?

I worked there through 1983 when Bill sold the company to Harman International.

And you still work at Harman.

Yeah, so I never really changed jobs, I worked at Harman through 2000. Then in January of 2000 I took a job at Digital Theater Systems (DTS) and stayed there for three years, and then I retired. That's the condition I am in now except that I come in here two or three days a week and have fun. I always tell them that it's really nice being paid for something that I would do for free.

That's really been the story of my engineering career. I have always loved electronics, and learned to love audio as I learned more about it. I think it's amazing to be able to do something you love and get paid for it.

Were you excited when you heard that Bill Putnam's sons were going to resurrect the company?

Oh yeah you bet.

It's been very successful.

I was very happy to see Bill taking interest in it. When we have discussions, I'm always impressed with how interested he is in making things as exactly like they were as possible. The products that he has done that are legacy products are so much like the originals that I don't think anyone could ever say that they don't sound just the same. There are a lot of people that still say that the old UREI products were a really great sounding product.

Do you remember Bill Jr. as a little boy?

Oh yeah. I remember when he was about six and his brother Jimmy was two or three.

Bill Jr. was obviously very bright, I was at there home many times, and Bill had a lab out at the house for years.

In closing, do you have favorite Bill Putnam story?

I have told this story a lot of times because I was so impressed when it happened, and now looking back I realize it is a metaphor for our relationship in the many years I had the privilege of working for Bill. When I had been working for Bill for about three months, in the winter of 1969, Bill asked if I would like to take a ride on his sailboat. It was a 38-foot ketch that he kept at Channel Islands Harbor. At that point in my life, I had not been on open ocean on a private yacht and was a little nervous, but Bill assured me that he knew how to sail--an understatement I later learned--and he was, after all, the boss. What could I say but yes? We met out at the harbor, and he showed me around the beautiful boat we were to take out to sea. He showed me things about sheets, cleats, booms, winches and other sailing mysteries and off we went.

About a quarter-mile out of the harbor, the air suddenly turned very white--opaque, in fact. I said, "What now?" He said, "We came out here to sail," and then he calmly took a note pad out of his pocket, jotted down the time and the compass heading, and we proceeded. Bill was as calm as could be and I was acting as calm as I could, given that I was pretty sure we were doomed. After awhile he made a turn, looked at his watch and the compass, and then wrote something else on the pad.

We were out for well over an hour and in that time he made a lot of turns and notes. I was thoroughly lost and disoriented. Presently, he said, "We should see the harbor entrance in five minutes." In five minutes, there it was. Like magic! All done with skill, confidence, a compass and a wristwatch. Yeah, he knew how to sail. That day set the tone of our relationship for the rest of the time I knew Bill. When he seemed calm he was. When he said things would work out, they did. I never worried again while Bill was at the helm.